Computer Ethics

Disruption, Cyberpractices, and Normative Pluralism

Saint Louis University

September 3, 2024

The Domain and Purpose of Morality

The Domain Morality

- Actions: right, wrong, obligatory, permissible

- Consequences: good, bad, indifferent

- Character: virtuous, vicious

- Motive: good will, ill will

The Purpose of Morality

- To promote the survival of society

- To resolve conflicts of interest justly

- To ameliorate human suffering

- To promote human flourishing

- To assign responsibility, praise, and blame to actions

Three Levels of Ethics

- Metaethics

- Normative Ethics

- Applied/Practical Ethics

Metaethics

Metaethics is the attempt to understand the metaphysical, epistemological, semantic, and psychological, presuppositions and commitments of moral thought, talk, and practice. (Sayre-McCord 2023)

For example:

- Are there moral facts?

- If so, can we know them?

- What does “good” mean?

Normative Ethics

The branch of ethics concerned with what makes an action good or bad, right or wrong.

Three major traditions:

- Virtue Ethics

- Consequentialism

- Deontology

Applied Ethics

Sometimes referred to as “special ethics.” Applied ethics extends normative ethics to specific domains of human life. For example:

- Biomedical ethics

- Business ethics

- Engineering ethics

- Environmental ethics

- Computer ethics

Problem of Normative Pluralism

At the level of normative theory, then, ethics appears deeply pluralistic and fragmented. How can an applied ethics go forward, given such diversity in the views it might apply? (Rehg 2017, sec. 1.2)

Dividing Normative Ethics in Two

- Ethics of Character (pre-modern)

- Virtue ethics

- Ethics of Conduct (modern)

- Consequentialism

- Deontology

Ethics of Character

Major figures: Plato, Aristotle, Confucius

Moral questions are focused on:

- Excellence

- Virtue and Vice

- Living a “good life”

Ethics of Conduct

Major figures: Bentham, Mill, and Kant

Moral questions are focused on justice and impartiality:

- prioritizes obligation and moral acceptability/unacceptability

- virtues play a secondary role

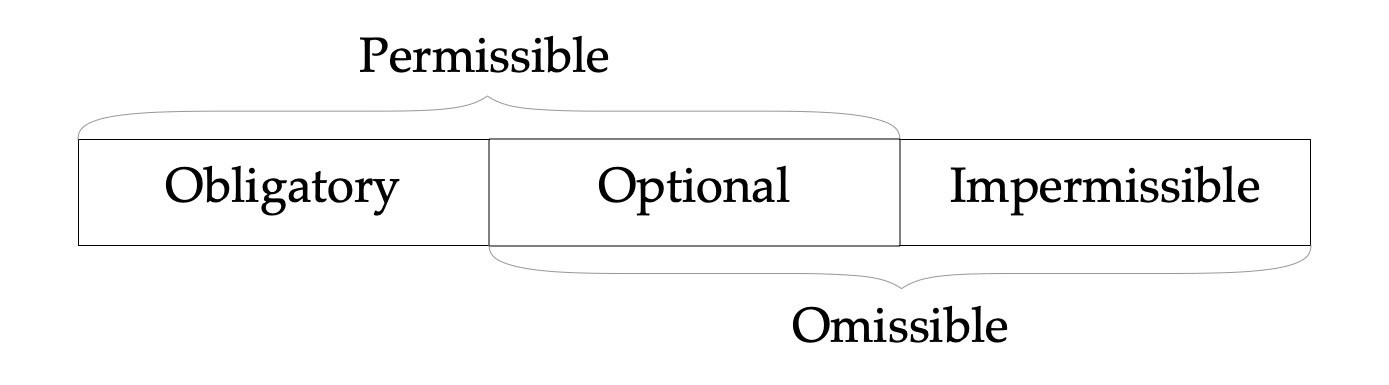

Diagram of deontic moral concepts

Here the important point is the contrast between the two ways of framing ethics—the premoderns favoring personal virtue, the moderns favoring impartial justice—and different ways of conceiving impartiality in modern philosophy. (Rehg 2017, sec. 1.2)

Three Ways to Address Normative Pluralism

Eclecticism: The toolkit/hodgepodge view

- Build multiple arguments using different normative theories

- Hope that many multiple theories render the same evaluation

Monism: Commit to one theory

Hybrid: Organize different normative principles into an integrated theory or structured method.

Rehg’s Proposal (A Hybrid Approach)

We think of cyberethics, as a form of applied ethics, as open to two distinct, though interrelated lines of inquiry:

- Is the cyberpractice morally acceptable, that is, does it treat all those affected justly?

- Is the cyberpractice ethically good, that is, does it contribute on balance to human well-being and the common good?

Rehg prioritizes (1) over (2), but a complete cyberethical evaluation will need address both questions.

Cyberethics and Disruption

Three Kinds of “Disruptive” Change

- ICTs change the way we engage in many activities and practices

- Expand the scope of certain activities

- Introduction of artificial agents

Social Practices and Cyberpractices

Social practices have increasingly become “cyberpractices.” I understand a social practice as any recurrent pattern of activity in which people intentionally cooperate in the pursuit of some end or set of goods. Social practices shape the bulk of our everyday lives—they structure our upbringing and education, our work and much of our entertainment, our production, distribution, and consumption of goods.

Social Practices and Cyberpractices

When ICTs shape a social practice in one or more of the ways described above, changing how people cooperate and the ends they pursue, that practice qualifies as a cyberpractice. Because ICTs depend on networks of production and distribution, even apparently solitary engagements, such as solitary video gaming, fits this social conception of cyberpractices.

Social Practices and Cyberpractices

- Social Practice

-

Any recurrent pattern of activity in which people intentionally cooperate in the pursuit of some end or set of goods.

- Cyberpractice

- A social practice changed or expanded by ICT or the introduction of artificial agents into social practice

Important Terms

The terms and definitions here comes from Rehg (2017, ch. 1). We will use these terms throughout the semester.

- Moral Triggers

- Morally problematic uses and effects of ICTs in social-institutional domains and practices, those places where new cyberpractices call for moral inquiry. An ICT should trigger moral reflection not only if it creates injustice or doubts about right conduct, but also if it threatens virtuous character or flourishing.

- Conceptual Muddles

-

New cybertech creates a conceptual muddle when it changes a social practice or activity in such a way that some concept or set of concepts connected with the practice or activity becomes unclear or contentious for members of the practice.

- Policy Vacuums

- A policy vacuum exists when two conditions come together: (1) some regular activity or area of social practice is of moral concern (2) standards of appropriate behavior and technological design for that activity or practice are non-existent, outdated, or poorly conceived.

- Moral Opacity

- Conceptual challenges in cyberethics are exacerbated by the “moral opacity” of many cyberpractices. A cybertechnology and its associated practices are morally opaque insofar as the people involved are unaware of morally problematic features, either because they lack knowledge of the technology itself or because they fail to notice the values embedded in the ICT design or use.

Rehg: Ethics-of-Respect Preview

- Identify a policy vacuum

- Who are the stakeholders?

- What are their values?

- Can we propose solutions to policy vacuums that all stakeholders can realistically subscribe to?

Social Practices and Cyberpractices