Mind-Body Problem: Part 2

March 20, 2025

Dualism

Human beings are composed of mind and matter

Physical/Material Entities

- Can be reduced to the language of physics and chemistry

- Are physical/material and have physical properties

- Occupying space (and time)

- Shape

- Extension

- Mass and density

- Chemical, electrical, magnetic and gravitational properties

- Are publicly observable

Mental Entities

- Can NOT be reduced to the language of physics and chemistry.

- Are non-physical/immaterial and so lack physical properties

- They occupy time but not space.

- They have no shape, extension, mass or density.

- They have no chemical, electrical, magnetic or gravitational properties.

- Are private — not publicly observable.

Two Major Types of Dualism

- Substance Dualism

- Human beings are made up of mind and body—two separate substances.

- Property Dualism

- Human beings are made up of a single substance: body. However, the body has both mental and physical properties.

Arguments for Dualism

Most arguments for dualism are based on Leibniz’s Law

Leibniz’s Law

- According to Leibniz’s Law \(x\) and \(y\) are numerically identical if, and only if, any property held by \(x\) is held by \(y\) (and vice versa).

- Symbolized: \(\forall x \forall y [(x=y) \to \forall P (Px \leftrightarrow Py)]\)

- Also called the indiscernibility of identicals

Arguments for Dualism: Basic Form

Arguments for dualism using Leibniz’s Law (typically) have the following form.

- 1.

- \(m\) has property \(P\).

- 2.

- \(b\) does not have property \(P\).

According to Leibniz’s Law if \(m\) has property \(P\) but \(b\) does not, then \(b ≠ m\).

- ∴ 3.

- \(b ≠ m\) (from 1 and 2 by Leibniz Law)

Descartes’ Argument from Doubt

I know for certain both that I exist and at the same time that all such images, and, in general, everything relating to the nature of body, could be mere dreams

.

– Descartes, Second Meditation

- 1.

- I can doubt that I have a body.

- 2.

- I can not doubt that I have a mind.

- ∴ 3.

-

My body is not my mind.

(from 1 and 2 by Leibniz’s Law)

Physicalist Response:

The argument commits the intentional fallacy: The mistake of treating different descriptions or names of the same object as equivalent even in those contexts in which the differences between them matter.

Physicalist Response:

Counterexample:

- 1.

- Lois Lane believes that Superman can leap tall buildings in a single bound.

- 2.

- Lois Lane does not believe that Clark Kent can leap tall buildings in a single bound.

- ∴ 3.

-

Superman is not Clark Kent.

(from 1 and 2 by Leibniz’s Law)

This goes back to our lesson on sense and reference. Leibniz’s Law does not apply here because the introspection argument appeals to propositional attitudes.

Argument from the Difference Between Mental and Physical Entities

[I have] a body that is very closely joined to me. But nevertheless, on the one hand I have a clear and distinct idea of myself, in so far as I am simply a thinking, non-extended thing; and on the other hand I have a distinct idea of body, in so far as this is simply an extended, non-thinking thing. And accordingly, it is certain that I am really distinct from my body, and can exist without it.

– Descartes, Second Meditation

Version 1:

- 1.

- My body is extended in space.

- 2.

- My mind is not extended in space.

- ∴ 3.

- My body is not my mind.

Version 2:

- 1.

- My mind is a thinking thing.

- 2.

- My body is not a thinking thing.

- ∴ 3.

- My body is not my mind.

Physicalist Response: Reject Premise 2 in both arguments.

Modal Arguments

Modal argument are based on the principle that identity is a necessary relationship. If \(a=b\) then it will be impossible to have \(a\) without \(b\).

Descartes: the possibility of a mind without body

- 1.

- I can exist without a body.

- ∴ 2.

- My body is not my mind.

Chalmers: the possibility of phenomenological zombies

A zombie twin is being physically identical to someone that lack consciousness.

- 1.

- My zombie twin is possible.

- 2.

- I am conscious.

- ∴ 3.

- My conscious not physical.

Physicalist Response: Reject Premise 1 in both arguments.

Dualism: How are the mind and body related?

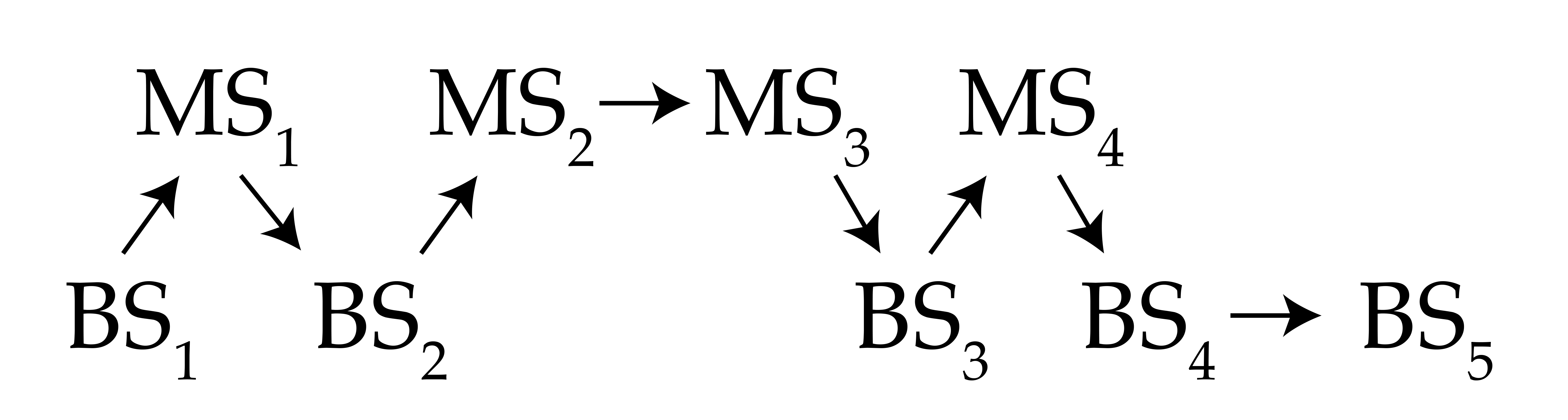

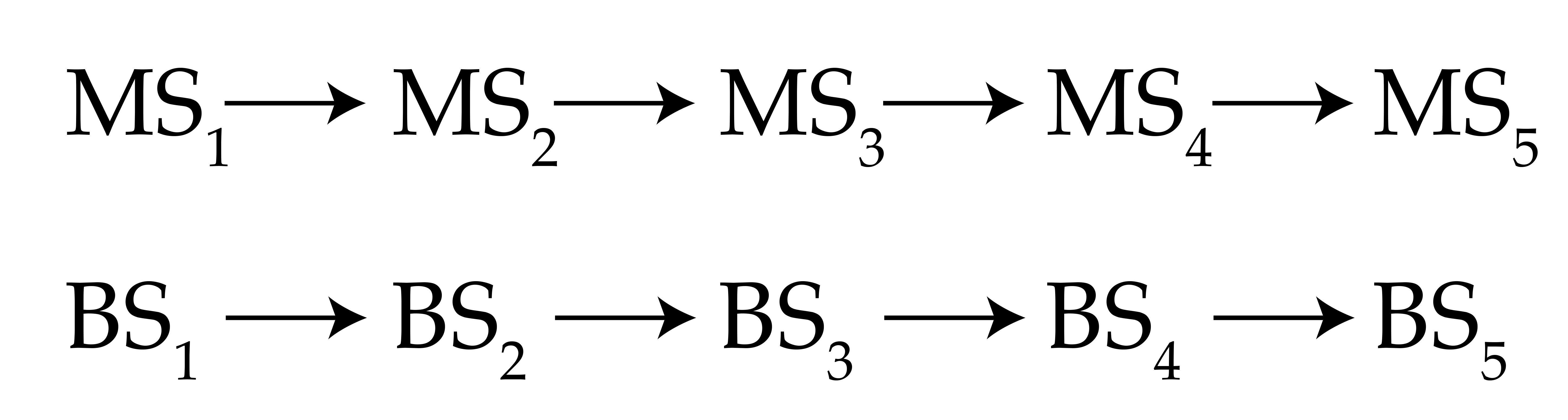

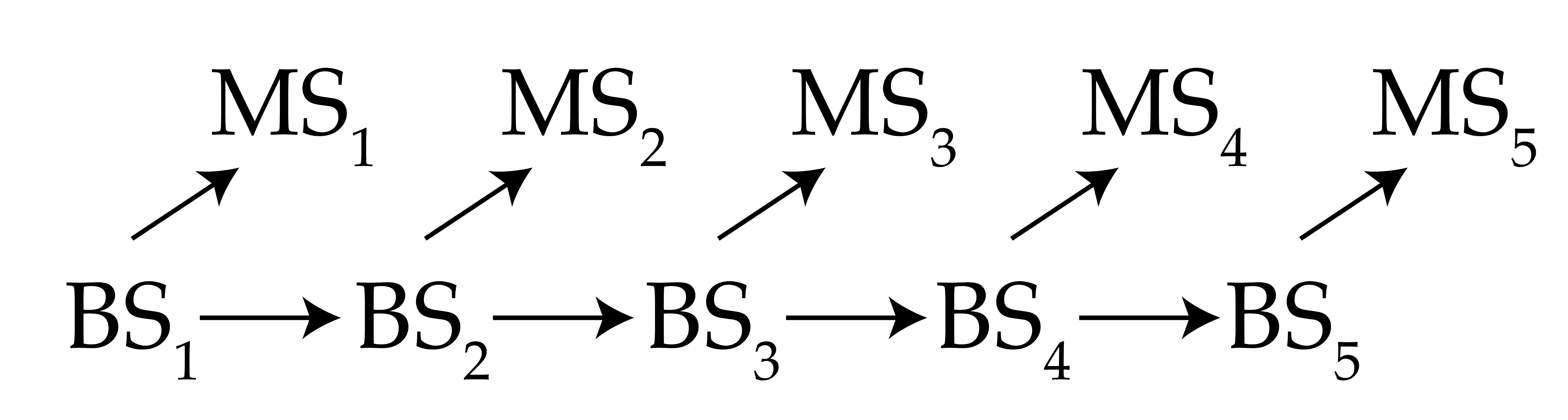

- Interactionism

- Brain states can cause mental states and mental states can cause brain states.

- Parallellism

- Brain states cause brain states. Mental states cause mental states. Brain states and mental states are coordinated by pre-established harmony.

- Epiphenomenalism

- Brain states cause mental states, but mental states do not casue brain states.

| Interactionism |  |

| Parallellism |  |

| Epiphenomenalism |  |

Difficulties for Dualism Interactionism

- Where do the interactions of the soul and body take place?

- How do the interactions occur?

- How can the idea of the mental causing the physical be reconciled with the principle of conservation of energy?