Existence of God

Part 2: Arguing for God’s Existence

March 27, 2025

Arguments for the Existence of God

Two Types of Argument:

- A Priori Arguments

- A Posteriori Arguments

A Priori Arguments

- An argument that depends on premises that can be known prior-to/independent-of experience: One need only clearly conceive of the proposition to see that it is true.

- ontological arguments

A Posteriori Arguments

- An argument that depends on premises that can only be known by means of experience of the world.

- cosmological arguments

- teleological arguments

- moral arguments

- arguments from religious experience

We will take a closer look at two argument families.

- Ontological Arguments (a priori)

- Cosmological Arguments (a posteriori)

Ontological Arguments

Key Concepts

- Great-making properties

- Necessity, Possibility, and Contingency

Great-making properties

- A great-making property is a property that makes anything better.

- As an example, Rowe contrasts wisdom with size:

- A person is always improved by gaining wisdom.

- A person is not always improved by gaining size.

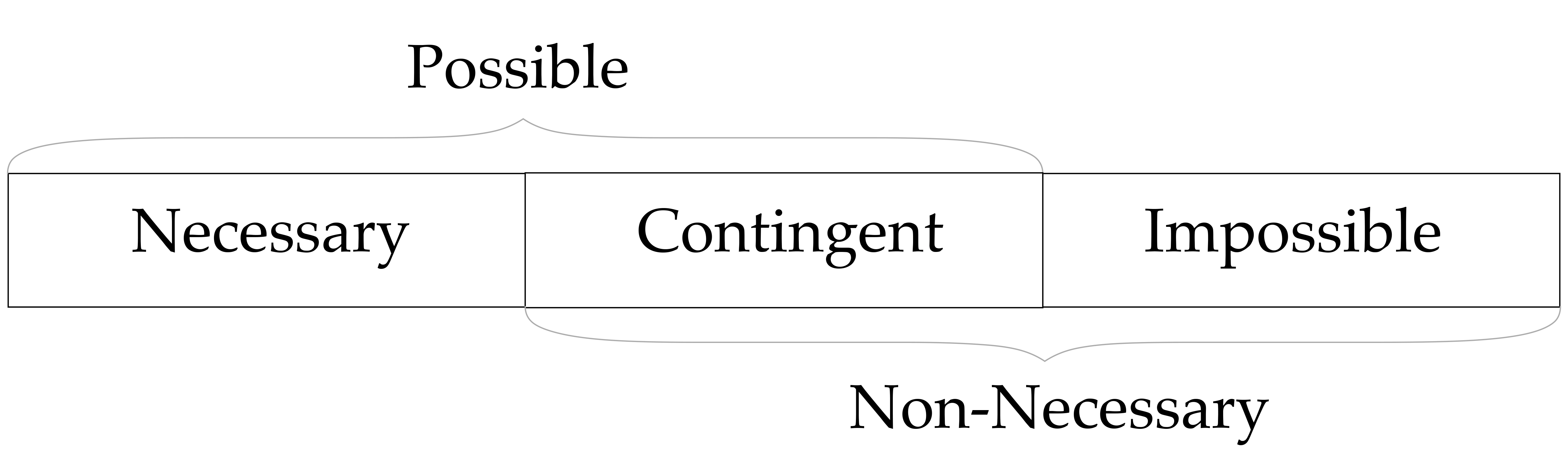

Necessity, Possibility, and Contingency

What do we mean when say that something is necessarily true?

The simple answer goes like this: Something is a necessarily truth if it somehow must be or has to be true.

But there are different senses in which a thing must be true. For example,

- Something might be inevitable. In that case it is the necessary consequence of things we cannot change. (E.g. If someone goes too long without eating, they will get hungry.)

- Something might be inalterable. Truths about the past are necessary in this sense. (E.g. World War I ended in 1919.)

- We might be referring to the influence of physical/causal laws. “What goes up must come down.”

We can also talk about mathematic and logical necessity.

- It is necessarily true that \(2+2=4\).

- It is necessarily true that: if all men are mortal and Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal.

- It is necessarily true that: some propositions are true.

Finally we can talk about what philosophers call broad logical necessity.

- Includes mathematic and logical necessity

- But also things like

- Nothing weighs more than itself

- No numbers are human beings

This last type of necessity—broad logical necessity—is what we are interested in when we discuss the ontological argument.

The relationship between necessity, possibility and contingency.

Possible World Semantics

- A linguistic tool philosophers use to talk about broad logical necessity

- A Possible world is:

- a state of affairs that is both maximal and consistent; a total description of the way reality could be

- “A possible world is a total way things could be or could have been, and a necessary truth is a proposition that is true in every possible world” (Konyndyk 2008, 16).

- A Possible world is NOT:

- Another universe/parallel world in the multiverse

- Another planet in our universe

Rowe’s Explanation for Anselm’s Argument

The argument

- 1.

- The greatest possible being (GPB) exists in the understanding.

- 2.

- The GPB could exist in reality (The GPB is a possible being).

- 3.

-

If something exists only in the understanding but could also exist in reality, then it could have been greater than it is.

(Existence is a great-making property.) - 4.

-

| Suppose the GPB exists only in the understanding.

- 5.

-

| The GPB could have been greater than it is. (2, 4, 3)

- 6.

-

| The GPB is not as great as it could be. (5)

- 7.

-

| The GPB is not the GPB. (6)

- 8.

- It is false that the GPB exists only in the understanding. (4–7)

- ∴ 9.

- The GPB exists in reality as well as in the understanding. (1, 8)

Objections: Parodies

Gaunilo’s Greatest Possible Island (GPI) and other parodies

- Parodies attempt to show that the argument leads to an absurd conclusion

- Responding to parodies:

- Some properties have intrinsic maximums and others do not.

- For example: the greatest possible angle (360°) vs. the greatest possible integer

- Can something finite and limited (like an island) have unlimited perfection?

Objections: Kant’s Criticism (Existence is not property/predicate)

Kant rejected premise 3.

- 3.

-

If something exists only in the understanding but could also exist in reality, then it could have been greater than it is.

(Existence is a great-making property.)

- Kant argued that the ontological argument treats existence like a property/predicate when it really isn’t.

Is existence a property/predicate?

Consider a table.

- Now abstract from it all of its properties except existence.

- Image that you could leave it existing without all the other properties.

- What would be left?

- Existence alone? But what is the difference between existence alone and nothing at all?

- If existence is a property/predicate we can simply add the property ‘existence’ to any concept and define things into existence.

Objections: God is Impossible

Some philosophers reject premise 2.

- 2.

- The GPB could exist in reality (The GPB is a possible being).

For example Logical Problem of Evil argues that God’s great making properties are inconsistent. (More on this later.)

Plantinga’s Ontological Argument

Plantinga’s version relies on alethic modal logic (the logic of possibility and necessity) and stated with possible world semantics.

A simplification of Plantinga’s argument (from W. L. Craig)

- 1.

- It is possible that a maximally great being exists.

- 2.

- If it is possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world.

- 3.

- If a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world.

- 4.

- If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.

- 5.

- If a maximally great being exists in the actual world, then a maximally great being exists.

- ∴ 6.

- Therefore, a maximally great being exists.

Cosmological Arguments

The Central Question

Cosmological begin with the question:

Why is there something rather than nothing?

The first three of Aquinas’ Five Ways

W1: The argument from motion/change

- 1.

- Something is moved by something else. (empirical observation)

- 2.

- Nothing moves itself. (metaphysical principle)

- 3.

- If A moves B and B moves C, then A moves C. (metaphysical principle)

- 4.

- There cannot be an infinite regress of moved things. (metaphysical principle)

- ∴ 5.

- There exists an unmoved mover. (conclusion A; from 1, 2, 3, 4)

- ∴ 6.

- The unmoved mover is God. (conclusion B; from 5?)

W2: The argument from efficient causation

- 1.

- There is a regular order of (efficient) cause and effect. (empirical observation)

- 2.

- Nothing is its own efficient cause. (metaphysical principle)

- 3.

- There cannot be an infinite regress of efficient causes. (metaphysical principle)

- ∴ 4.

- There exists a first efficient cause. (conclusion A; from 1, 2, 3)

- ∴ 5.

- The first efficient cause is God. (conclusion B; from 4?)

W3: The argument from contingency

- 1.

- Somethings are contingent (capable of existing or not existing) (empirical observation)

- 2.

- If all things are contingent then there was a time when nothing existed. (metaphysical principle)

- 3.

-

| Assume: that all things are contingent. (assumed premise)

- 4.

-

| But then nothing would exist now. (from 2, 3)

- 5.

-

| This is clearly false. (from 1, 4)

- ∴ 6.

- Something is necessary (not-contingent) (from 3–5 by reductio ad absurdum)

- 7.

- Everything that is necessary is either necessary because of something else or necessary in itself. (metaphysical principle)

- 8.

- There cannot be an infinite regress of things necessary because of something else. (metaphysical principle)

- ∴ 9.

- Something is necessary in itself. (conclusion A; from 6, 7, 8)

- ∴ 10.

- God is that which is necessary in itself. (conclusion B; from 9?)

Objections:

- If these arguments succeed, how do we know that the unmoved mover, first efficient cause, or thing necessary in itself, is God?

- How do we know that there is only one unmoved mover, first efficient cause, or thing necessary in itself?

The Kalām Cosmological Argument: What started it all?

Argument Part 1

- 1.

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- 2.

- The universe began to exist.

- ∴ 3.

- The universe has a cause.

Support for Premise 1

Craig says that this premise is intuitively obvious

Support for Premise 2: Philosophical Support

Supporting Argument 2.1

- 2.1.1

- An actually infinite number of things cannot exist.

- 2.1.2

- A beginningless series of past events involves an actually infinite number of things.

- 2.1.3

- ∴ A beginningless series of past events cannot exist.

Support for Argument 2.2

- 2.2.1

- An actually infinite collection of things cannot be formed by successive addition.

- 2.2.2

- The series of past events is a collection of things formed by successive addition.

- 2.2.3

- ∴ The series of past events cannot be actually infinite.

Support for Premise 2: Scientific Support

- The Success of Big Bang Cosmology

- The Failure of Alternative Models

Argument Part 2

- 1.

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- 2.

- The universe began to exist.

- ∴ 3.

- The universe has a cause. 4. If the universe has a cause, that cause is uncaused, beginningless, changeless, immaterial, timeless, spaceless, unimaginably powerful, and personal.

- ∴ 5.

- A personal Creator of the universe exists, who is uncaused, beginningless, changeless, immaterial, timeless, spaceless, and unimaginably powerful.

Objections:

- If the arguments succeed, how do we know that the cause of the universe is God?

- How do we know that the cause of the universe is still around?

- How do we know that the cause of the universe is a single conscious agent?

- Causality is logically compatible with an infinite, beginningless, series of events.

- If everything has a cause of its existence, then the cause of the universe must also have a cause of its existence.

The Contingency Argument: Why is there something rather than nothing?

- 1.

- A contingent being exists.

- 2.

- This contingent being has a cause or an explanation of its existence.

- 3.

- The cause or explanation of its existence is something other than the contingent being itself.

- 4.

- What causes or explains the existence of this contingent being must be either other contingent beings or include a noncontingent (necessary) being.

- 5.

- Contingent beings alone cannot cause or explain the existence of a contingent being.

- 6.

- Therefore, what causes or explains the existence of this contingent being must include a noncontingent (necessary) being.

- ∴ 7.

- Therefore, a necessary being exists.